As the research community grapples with a range of projects considering the culture of research from a variety of angles, Policy Manager Rachel Persad reflects on GuildHE’s work in this area and looks forward to supporting the inclusion of multiple perspectives in this work.

Whether you welcome or are sceptical of the focus on research culture it is undeniably having it’s moment in the spotlight. Personally, I believe it is right to pay attention to and place great value on how research is done, how we collectively treat the people involved, and consider the wider effects on all involved of the incentives that are prioritised in research and innovation.

The word on the (research) street

In recent weeks the funders of the Research Excellence Framework have confirmed the details of the project commissioned to deeply consider how research culture, people and environment can be effectively assessed. It is appropriate that the whole exercise has been delayed by a year to 2029 to allow this project to not only be completed and draw conclusions, but also for the indicators developed to be piloted. As one of our member institutions said, reaching an appropriate assessment of research culture is simply ‘too important to rush’.

Vitae have published their report on research culture in the UK, and developed a Research Culture Framework that is worth a look. This is really welcome, will support the development of the Good Practice Exchange requested by government, and presumably inform Vitae’s thinking on PCE, given that they and Technopolis will be delivering the pilot.

Running alongside these activities, the UK Committee on Research Integrity are leading focus groups and workshops to explore what indicators might be developed to measure research integrity, and if they can be developed at all. We are pleased to be advisors on this project. It is great to see the work we commissioned on indicators with UKRI and Cancer Research UK be lifted off the page in this way. And as we have written on this site before, research integrity is a central pillar of research culture, perhaps the most important one for institutions that are in the early stages of developing a research environment.

Including different perspectives

In all our work on these issues we are committed to ensure that the perspectives of all researchers and research institutions are included. We have demonstrated this through our projects with peer researchers to explore the experiences of ethnic minority postgraduate students, by raising the importance of EDI in the development and evolution of concordats, and by consistently advocating for the distinctive perspectives of smaller and specialist institutions in consultations such as that on the REF People, Culture and Environment element.

Additional investments targeted at enhancing research culture by Research England have been vital. These funds were equitably distributed through QR (the strategic institutional funding stream) and most importantly allocated with a minimum value (£10k) which can actually lead to tangible action.

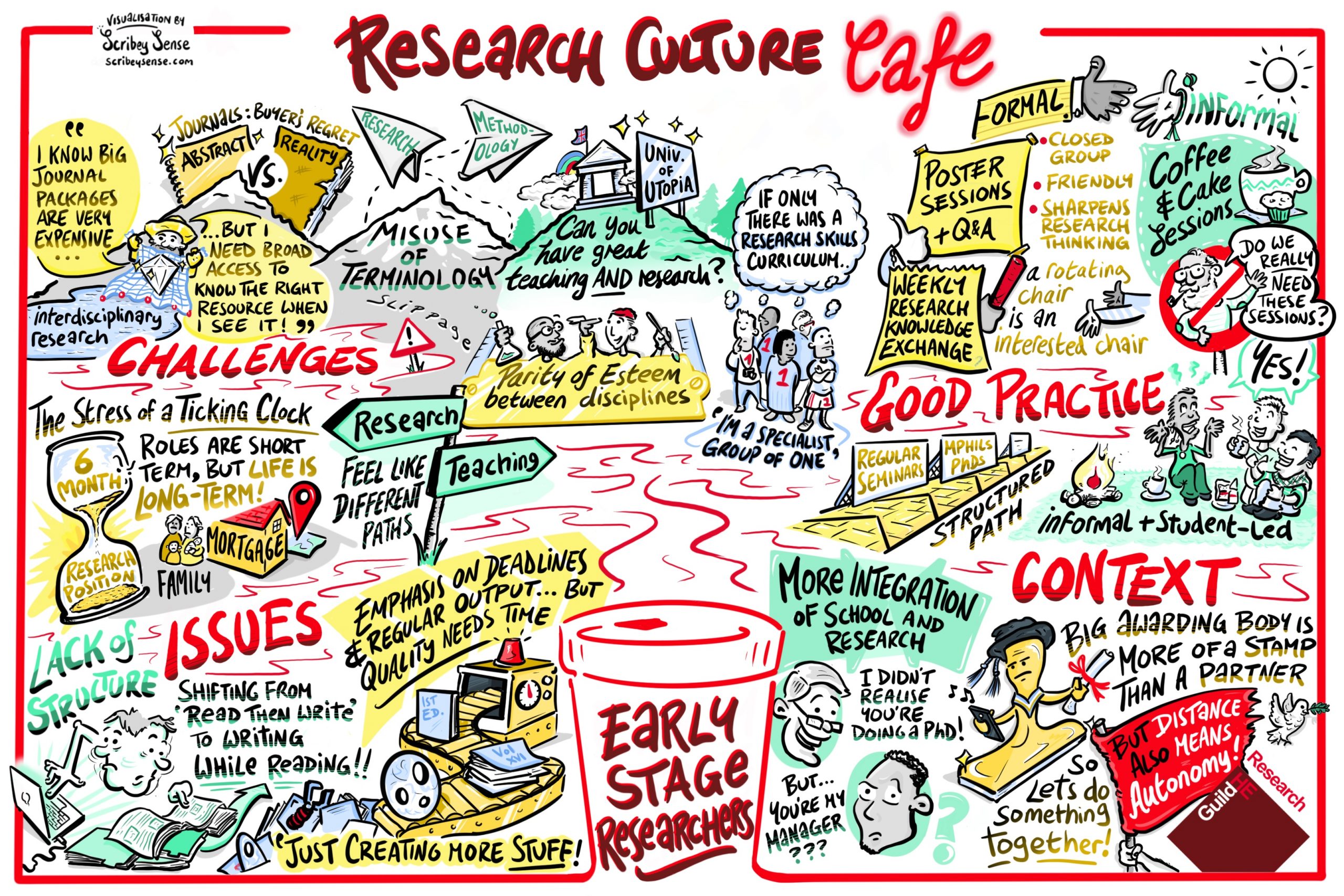

This enabled our members and GuildHE itself to do additional work to examine and improve research culture at smaller and specialist institutions. GuildHE devised a series of activities including workshops on resilience and allyship for staff, training sessions on inclusive approaches to research, and Research Culture Cafés.

You can see the conversations these cafés generated in three engaging and vibrant graphics on the project pages we’ve just published. We have reflected on some of the key differences we identified between what researchers at smaller and specialist institutions were raising compared to previous work done by the Wellcome Trust and others, and why that might be.

One size won’t fit all

We will continue to advocate for and represent the perspectives of researchers and research support professionals at smaller and specialist institutions – it’s our job after all, but it’s also really important that we don’t lose sight of the complexity of the community all these projects are looking to serve.

Typically these research environments are small in scale, whilst being excellent and ambitious in scope, and sited within smaller scale institutions and / or institutions with a particular disciplinary focus. The research office may be a single person, or perhaps a small group of professionals, and there may not yet be a member of the senior management team with exclusive responsibility for research.

External research income is low compared to the rest of the sector, and / or the disciplinary focus is such that income is derived from non-traditional sources, such as arts councils. Quality-related funding is essential to these institutions, although if they are very emergent they may not yet have submitted to the REF and will be sustaining research without it. Competitive research grants are challenging to achieve, for a variety of reasons, and sometimes eligibility for funding can be restrictive for less traditional institutions – as we explored in a recent briefing.

Visibility can also be a problem. If a monotechnic, their expertise and excellence can be easily missed, with many league tables and write ups of key achievements such as the REF in the press not including them – they are an outlier, a challenge to absorb into a wider narrative about UK Research PLC.

Furthermore, from our research into our postgraduate student body we also know those in early stages of their research careers share different characteraistics to the rest of the sector; they are more likely to be self funded and be mature students with other work and personal commitments. Again, this makes their experience quite distinct. As these early stage researchers may be consolidating successful careers in industry and professions, they also come to research environments with different expectations, and perhaps different goals than a researcher that has taken a more standard path.

We also know that researchers at smaller and specialist institutions are particularly time poor, and our members are dispersed geographically, in some cases located in ‘cold spots’ – regions without other higher education or research organiations present. They are in teaching intensive institutions where research time is at a premium and teaching commitments prevent many from taking part in sector discussions. Researcher isolation is a real and constant problem.

All these factors makes the experience of doing research quite distinct from a multi-faculty and research intensive institution. It is vital that indicators developed, strategies devised, and concordats drafted keep the full diversity of research organisation, locations, and people in mind.

The many advantages of inclusion

Inclusion is not easy, it does make the picture more complex, but in that complexity there is much to celebrate – richness of experience, diversity of perspectives, access to different skills, and novel approaches and questions. We are ready and willing to support all the work in research culture and look forward to bringing our diverse member institutions with us.

Recent Comments